The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design / Justin Chan Photography

More often than not, universities include acres of asphalt parking lots that create polluted stormwater runoff. To create a more walkable and environmentally-responsible campus, the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia, partnered with the Kendeda Fund, a foundation, to transform a parking lot and street into the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, the largest building in the southeastern U.S. to be net-positive in terms of energy and water use. Landscape architects with Andropogon integrated an innovative water management system that captures and reuses 100 percent of stormwater runoff from the building, and also cleanses and reuses building greywater in the ecological landscape.

Background:

The $30 million, 46,800-square-foot Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design includes classrooms, lab spaces, and gathering areas. The building is the first to be certified in the southeastern U.S. under the Living Building Challenge, which is one of the world's most rigorous sustainability rating systems.

The Living Building Challenge calls for structures and landscapes to be regenerative, meaning they give back more to the environment than they use. To be certified, a project must meet criteria in seven areas: beauty, place, equity, water, energy, materials, and health. Meeting the criteria requires an integrated planning and design team that can bring building and landscape together into one system.

Andropogon, which led the landscape architecture and ecological design components of the project, partnered with lead architects at Lord Aeck Sargent, design architects with the Miller Hull Partnership, and a range of specialized engineers with Newcomb-Boyd, Uzun+Case, Long Engineering, and Biohabitats.

The 1.35-acre landscape surrounding Kendeda is adjacent to the 8-acre Eco-Commons, a demonstration project that uses the campus landscape to grow food, conserve natural resources, and reduce campus stormwater runoff by 50 percent.

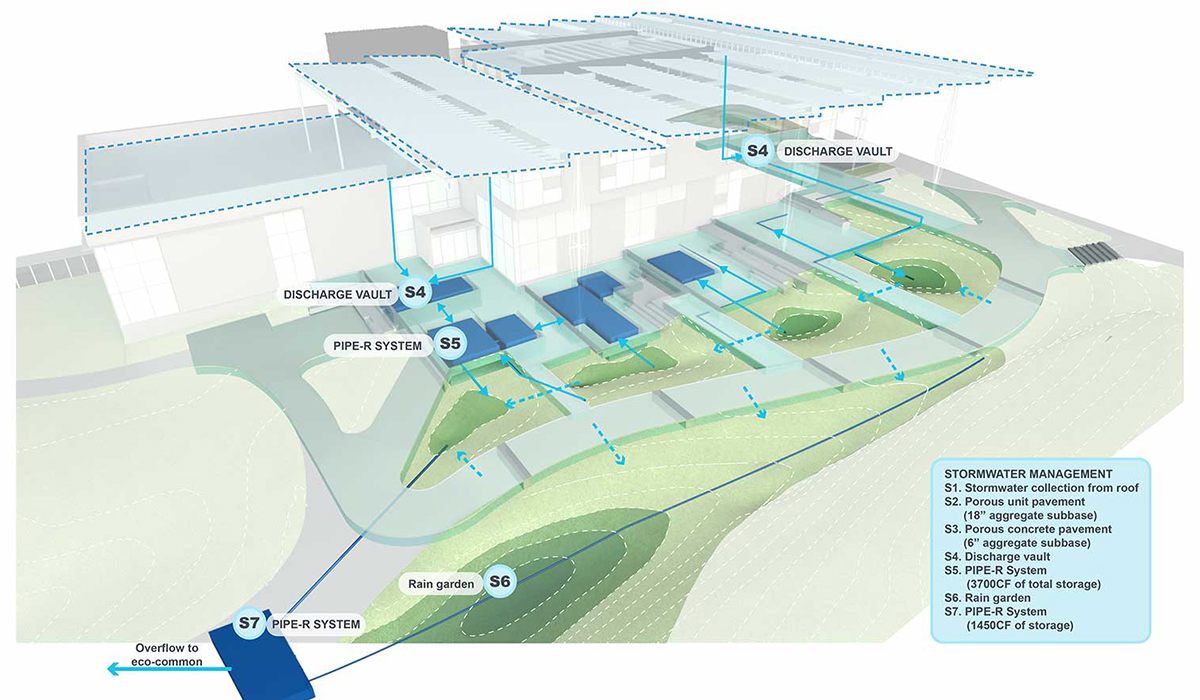

Both the building and surrounding landscape harvest an estimated 460,000 gallons of water each year. A number of features help the university capture and manage this amount of water:

- The cantilevered canopy roof was designed to be large enough to hold 917 photovoltaic (PV) panels, which generate 140 percent of the building’s energy needs, and also provide shade in Atlanta’s steamy summers. The PV panels were angled to divert some stormwater runoff into a 50,000-gallon cistern, which collects water for cleansing and reuse in the building. Stormwater from the roof that is not diverted to the underground cistern is directed to surrounding constructed wetlands for cleansing and infiltration.

- The Living Building Challenge required that 20 percent of the site be used for agriculture. A 5,000-square foot rooftop farm, comprised of pollinator gardens, blueberry orchard, and a range of agricultural beds, grows food while capturing stormwater. At ground level, there is also a 5,350-square foot edible landscape where students and visitors can pick fruit and berries from trees, shrubs, and perennials year-round.

- Throughout the pathways surrounding the building, Andropogon incorporated pervious pavers and concrete that absorb stormwater and infiltrate it into the ground.

- A series of rain gardens around the building manage stormwater runoff from adjacent pavement and provide habitat for pollinators and wildlife. These gardens refer to two habitats that are native to the local ecoregion: mesic woodland and seepage wetland zones.

- The landscape was also designed to reuse 95 percent of the building’s grey water. Grey water from sinks and showers is diverted to constructed wetlands, filled with native plants, that clean and filter the water before directing it to a drain field where it is infiltrated back to the groundwater. According to Andropogon, one wetland was situated at the entrance of the Kendeda building in order to clearly demonstrate the power of nature to clean water.

One goal of the Living Building Challenge is zero waste, so the landscape also captures human waste collected in the building. Conventional flush toilets were replaced with foam flush toilets and waterless urinals that direct waste to composters in the buildings’ basement. There, waste is transformed into leachate that is discharged into a drain field at the low end of the landscape.

Lastly, the landscape was also designed to further reduce building energy use. Andropogon incorporated strategically-sited trees and climbing vines that create shade, thereby cooling the air and building facades.

- The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, Andropogon

- Georgia Tech’s Kendeda Building Sets a High Bar for Regenerative Design, Metropolis

- Eco-Commons Construction Begins Next Week, Georgia Tech

- A structure that produces more energy than it uses? In the deep south? Welcome to the Kendeda building, Atlanta Magazine

- Reuse/redevelop brownfields and grayfields, including for open space.

- Promote or require water conservation and water reuse technologies.

- Incentivize urban and suburban agriculture.

- Require new development to retain stormwater on site.

- Incentivize planting of locally/regionally appropriate and biodiversity-supporting vegetation.

- Incentivize healthy soil management practices.

The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design / Andropogon